Carlisle Indian Industrial School

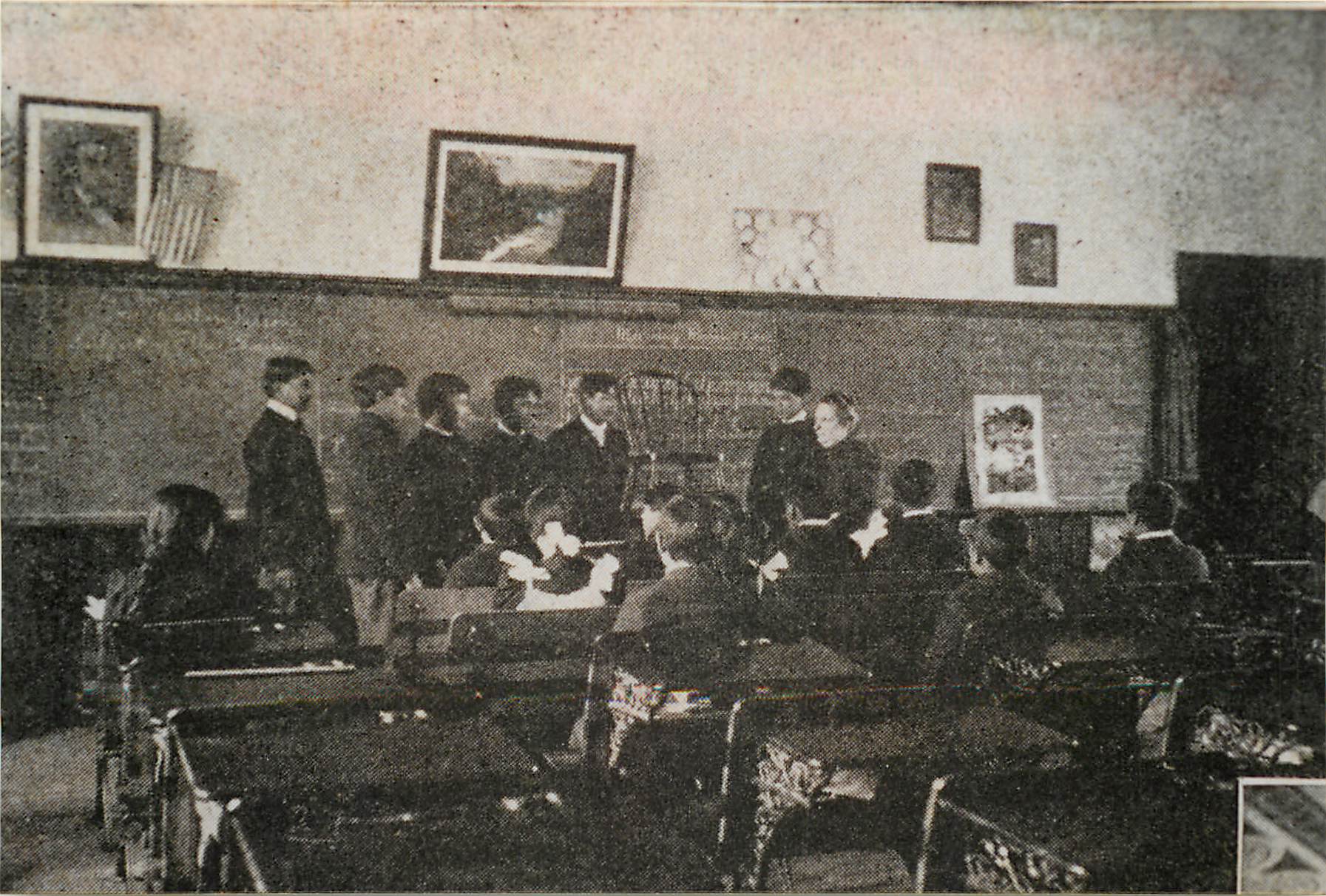

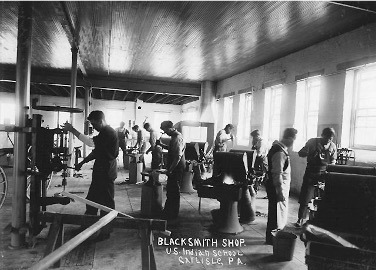

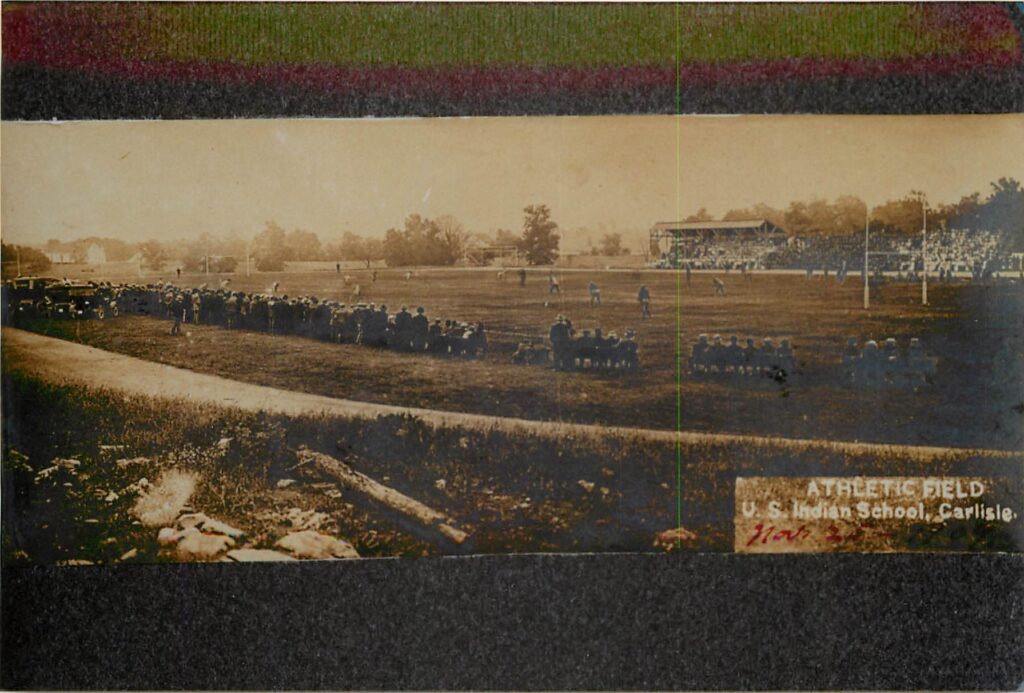

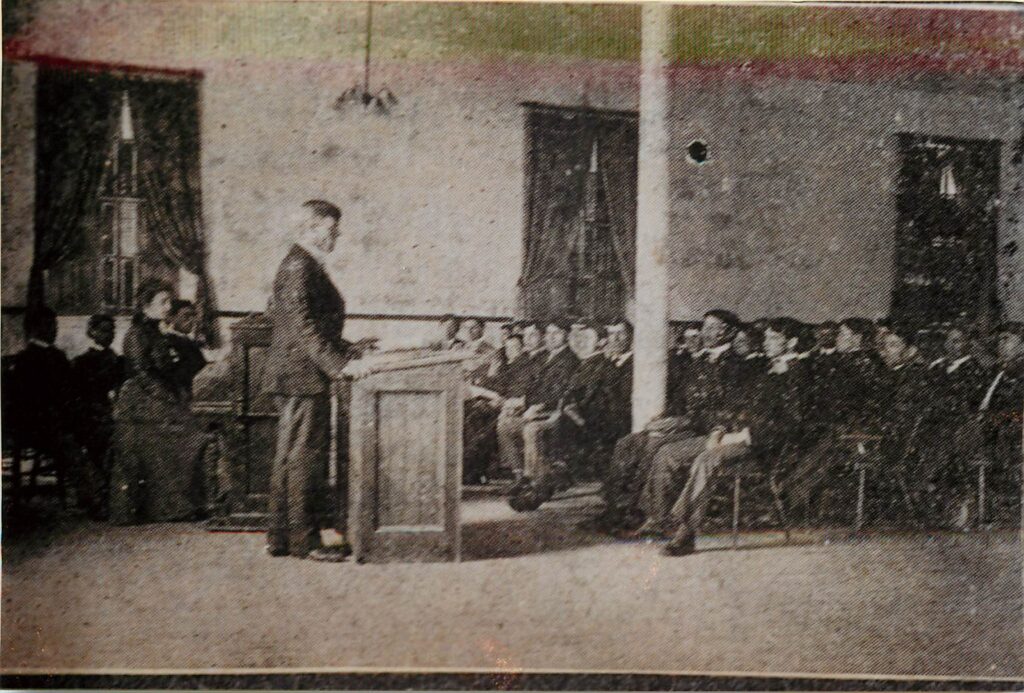

Above photos from John White’s personal scrapbook of Carlisle Indian Industrial School. c1909.

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School (1879 -1918) was the first all-Indian, off-reservation, federal Indian boarding school, started in 1879 by Civil War veteran, Lt. Col. Richard Henry Pratt.

Read more...

Pratt was in charge of Indian prisoners in Ft. Marion, Florida, when he began his grand plan of transforming Indians by educating them to be like white men. He started out at the Hampton Institute in Virginia, an existing Indian boarding school that also had freedmen in its student population. Differing views on what to do with Indian students prompted Pratt to part ways with Hampton’s founder, Gen. S.C. Armstrong. He would venture to Pennsylvania to a vacant military base with a handful of former Ft. Marion prisoners.

He eventually took children “hostages” to ensure good behavior of the Oglala & Brule Sioux, who were feared to raise up in rebellion against the U.S. Calvary. While he argued that it was cheaper to educate Indians than to go to war with them, most expenses for Carlisle and other federal Indian boarding schools were paid for by monies accrued from the sale of Indian lands.

He set off with dozens of children and took them over a 1,000 miles by train, across the country to a foreign land.

They arrived at the Carlisle Barracks in central Pennsylvania, the very place where the U.S. Calvary was trained to fight Indians and seize their lands (see Fear-Segal, J., 2016, p 8).

Dispossessing Indians of their lands across the U.S. would go hand in hand with distinguishing their existence by assimilating their children into white society. Pratt’s intentions were to save the Indian through civilization and assimilation and in doing so, would destroy their cultures and identities.

“Kill the Indian, save the man,” is what Pratt became known for. But this contradiction, as N.Scott Momaday reminds us, is similar to the old sentiment; “The only good Indian is a dead Indian,” in that it reflects the whole of Indian-white relations whereas the Indian is not seen as a man, but as an “inferior creature who can only become a man if his natural identity is destroyed” (Momaday, 2016, p 45).

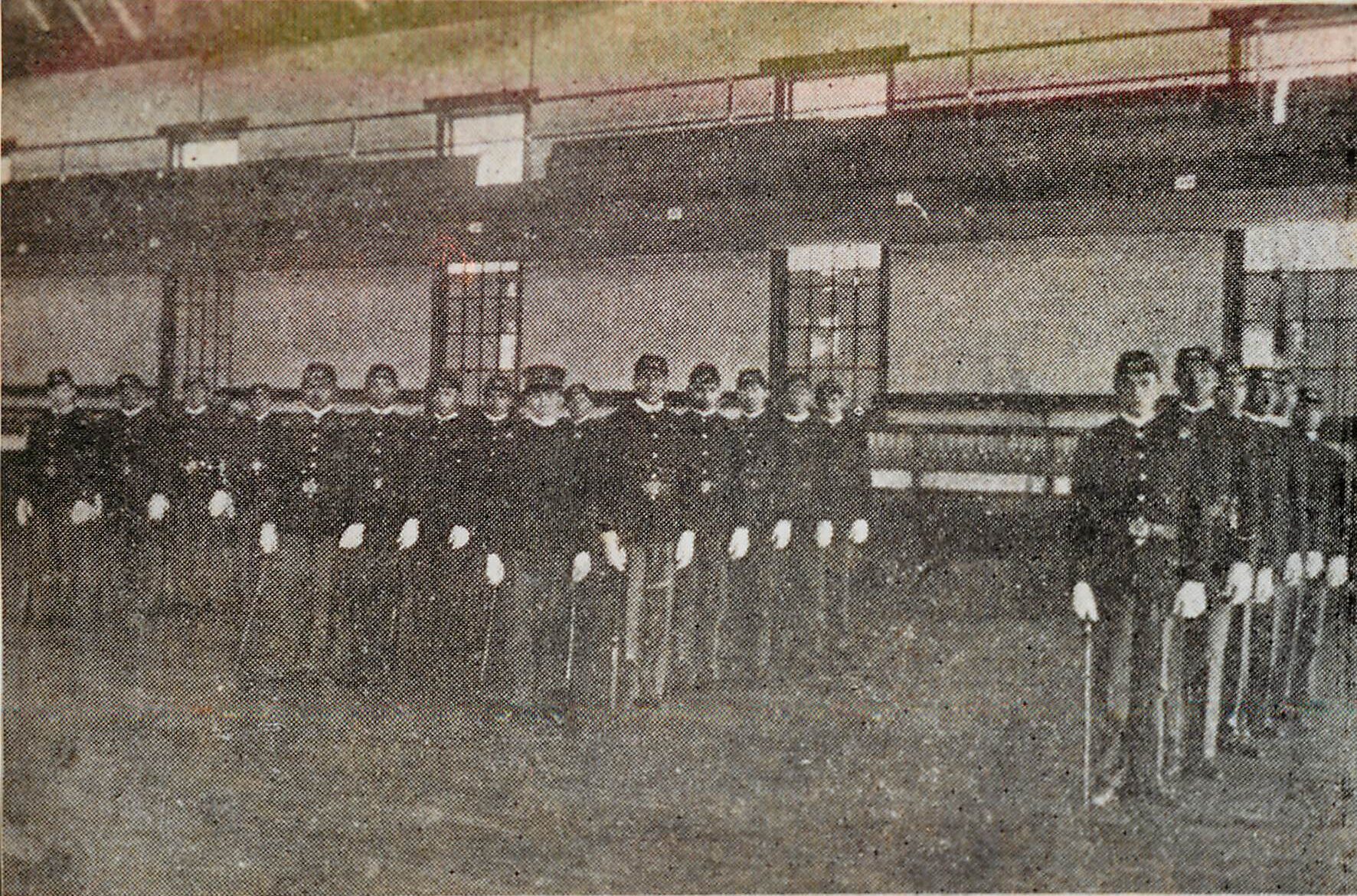

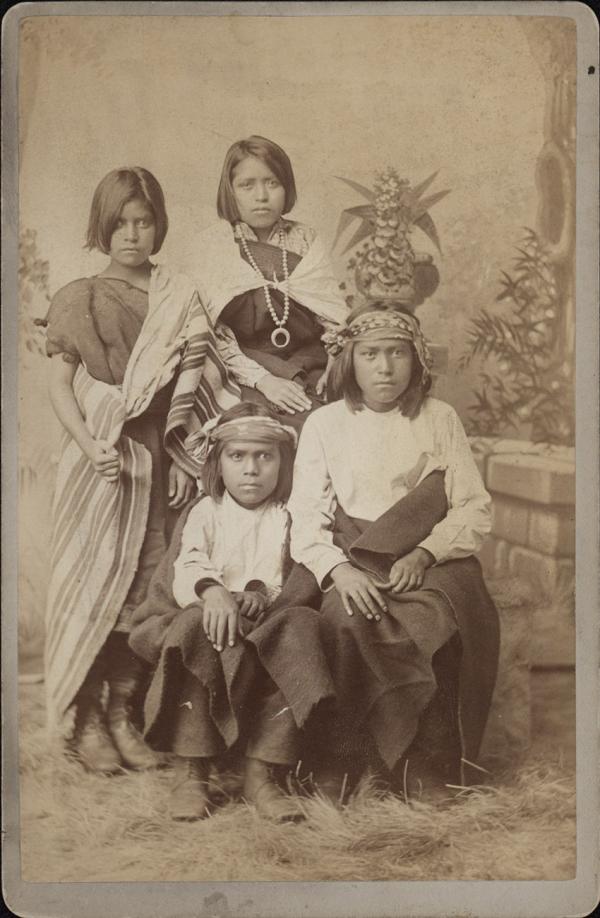

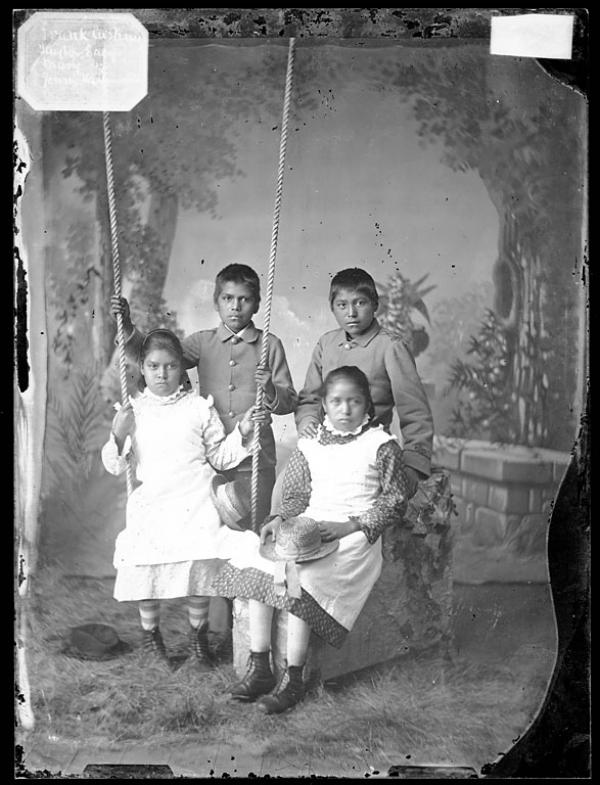

Pratt often took advantage of showcasing newly arriving children in the clothing, jewelry, blankets, and other cultural attire they arrived with, juxtaposing them in propaganda photos that showed their transformation, and thus, his success in erasing their Native identities.

Several of these photos were sent as postcards (see above middle photo) to potential donors to further Pratt’s cause of civilizing and assimilating Indian children.

The photos to the right, taken by school photographer John N. Choate, are of Zuni Pueblo children upon arriving in 1880, next to the same children photographed sometime afterward.

One of those children was Trawaeatsalunkia / Taylor Ealy who died July 10, 1883 of Typhoid Fever while on outing with Dr. Taylor Ealy. His three year registration period at Carlisle was up and he was supposed to return home July 31. Dr. Taylor Ealy had been a teacher at Zuni Pueblo and appears to have adopted the young boy, making him his namesake. When young Taylor died, Pratt instructed the Doctor to bury Taylor in Schellsburg where he lived and to send him the bill. It appears the Doctor did just that. Unusual for outing deaths, there is a family plot for the Ealy’s at the Schellsburg cemetery, with a small stone erected at Trawaeatsalunkia’s gravesite.

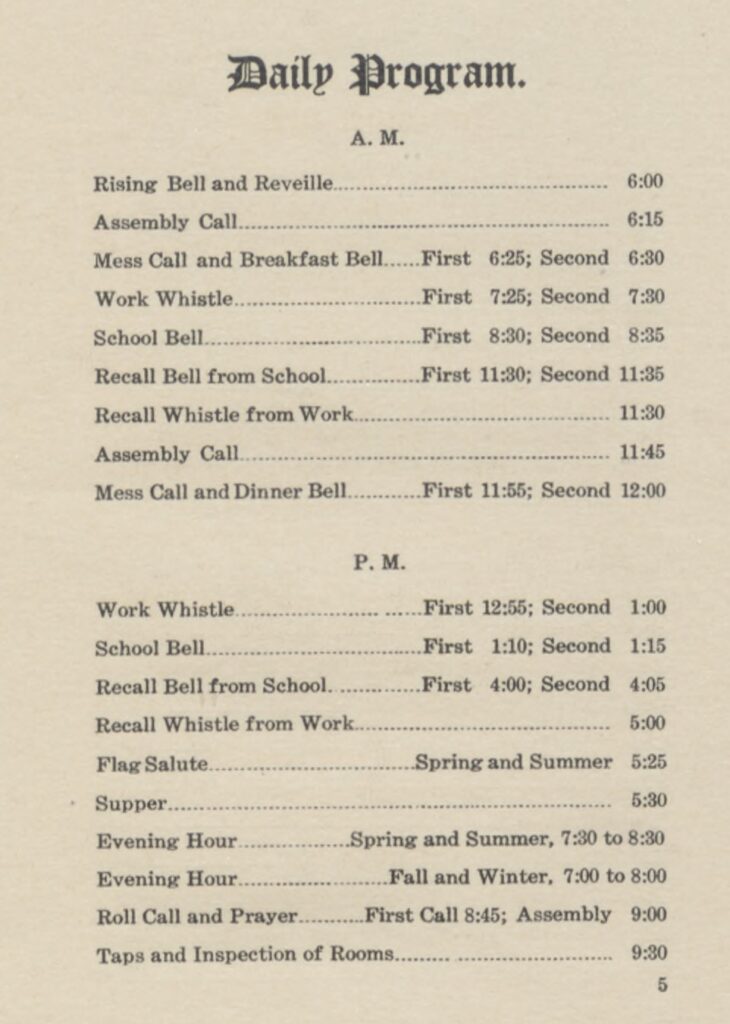

Students were to maintain a strict daily schedule, were responsible for the upkeep of the school working as cooks, dishwashers, cleaners, and working the school farm for their food.

Read more...

Upon arrival, any identifying markers of their Indigeneity were stripped away; their clothing was replaced by military style uniforms, their hair cut, and new English names arbitrarily given to reflect American individuality.

Students in the early years were less likely to speak English, especially those coming from western regions.

Students were older in later years, averaging 16. Many came from other smaller Indian boarding schools, like the Lincoln Institution in Philadelphia, Thomas Indian School in New York etc.

Carlisle finally closed in 1918 after almost 40 years and between 8-10,000 students were subjected to its mission of “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.” Carlisle created generations of Native peoples disconnected from their cultures, languages, and lands.

The last survivor of Carlisle, Andrew Cuellar, died in 2003. Through archival documents and oral history, there are no two experiences of Indian students that were the same. Experiences are dependent on the time period, policies and practices of the school, and what, if any, stories survivors chose to share. Some passed on fond memories of a place where they made life long friends and learned to read and write. Others suffered loneliness, abuse, and tried to run away.

Whatever their experience were, they belong to the students who endured an institution designed to take away their Indigenous identities. We can only try to piece together narratives from bits and pieces of archival documents and from the scant oral histories passed down.

Above images from John White’s personal scrapbook, Carlisle Indian School. c1906 – 1909.

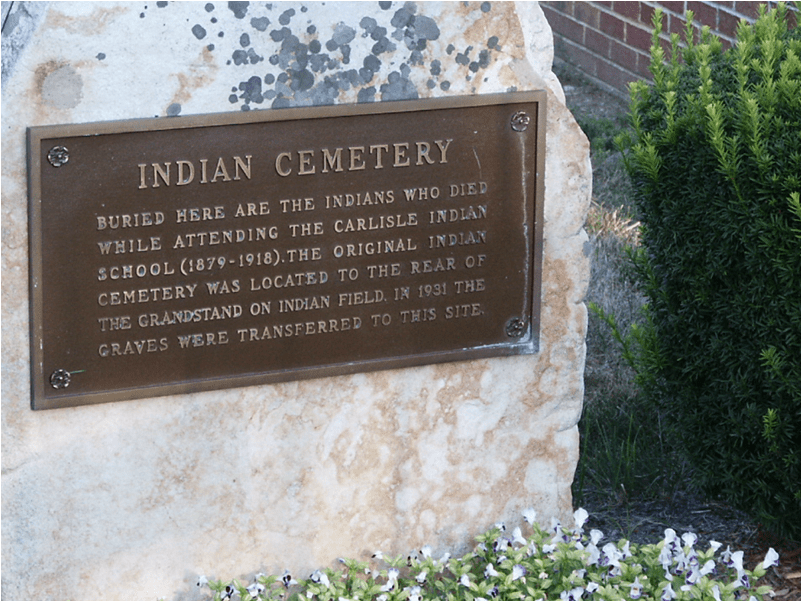

Carlisle Indian School Cemetery

Here are six rows of children. How

Symmetrical the gray array.

The names are dim and distant now.

We come and go, and here they stay.

Please pray they rest, and bless each name,

Then reckon innocence and shame.

(N.Scott Momaday, 2016).

There are close to 200 gravesites at the Carlisle Indian School cemetery on the grounds of the former school and the current U.S. Army War College at Carlisle Barracks.

Though they often died of diseases like Typhoid fever and Tuberculosis, the school administration would place the blame on the Indian’s already poor health due to their uncivilized living conditions at home; they must have brought the disease with them. To prevent too many deaths at the school, the sick and dying were sometimes sent home and didn’t always make it.

Read more...

Prominent chiefs and other parents requested the return of their children when they heard of numerous deaths at the school. No one listened. When their own children fell ill, they requested their children be sent home. No one listened. When their children died, they requested their bodies be sent home for burial. No one listened.

Some of those children are still buried in the school cemetery and in cemeteries scattered throughout the region.

However, since 2017 relatives have been reclaiming their children, but not without complications.