The Outing Program

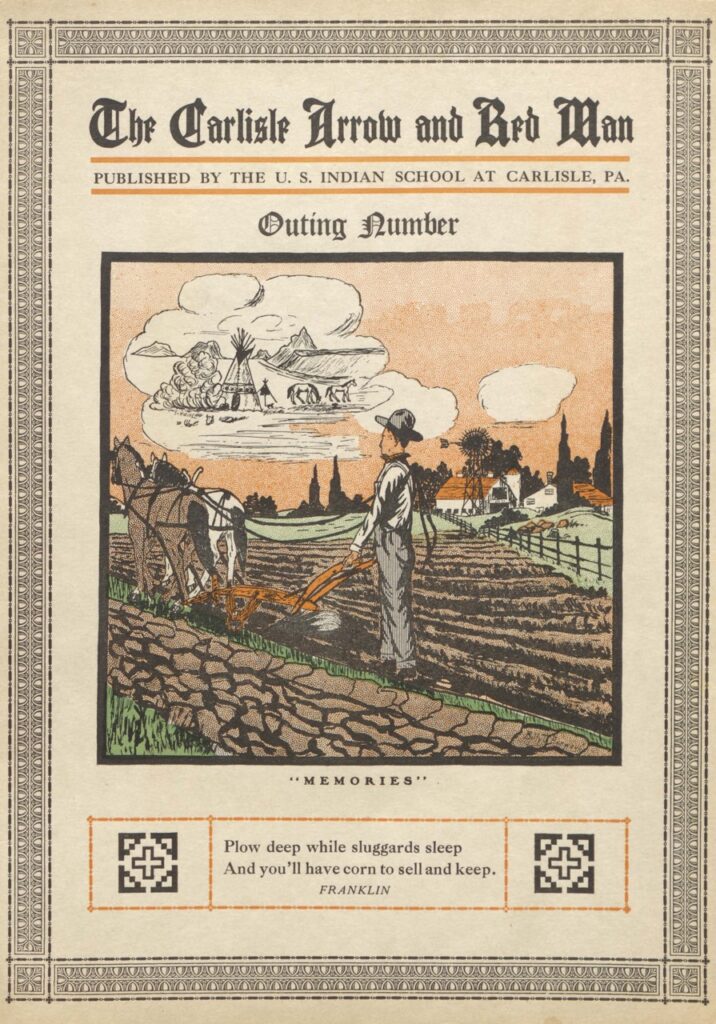

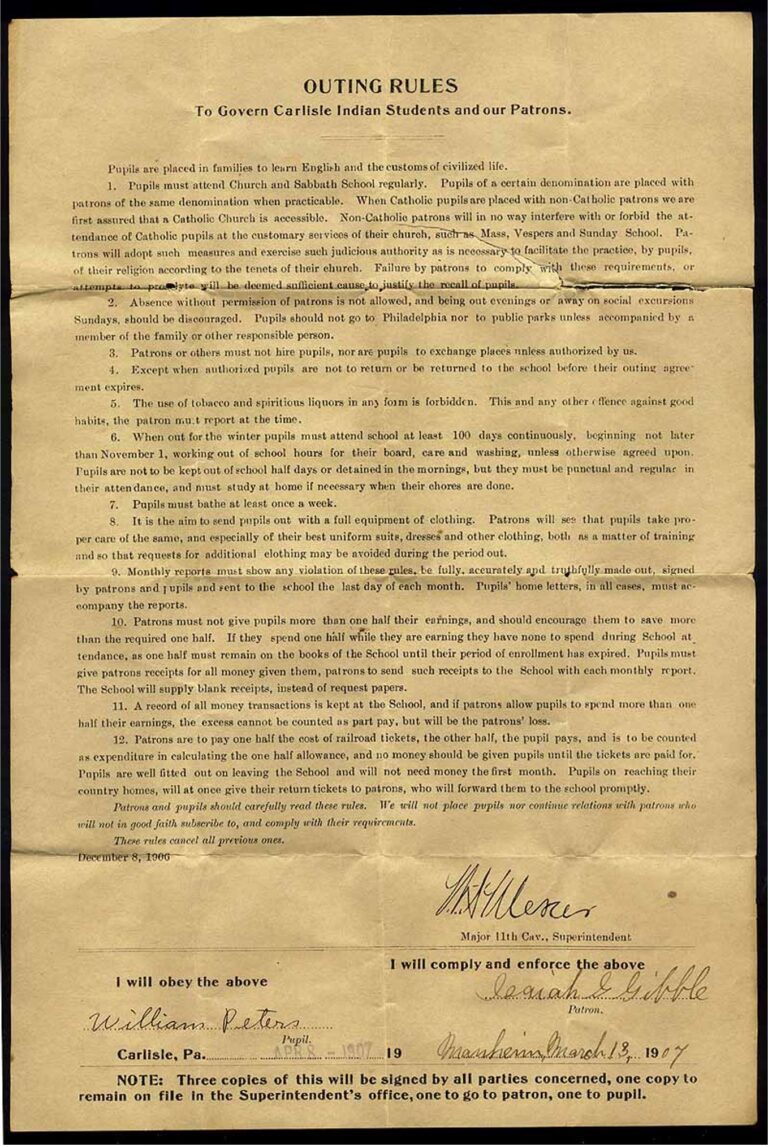

To further assimilate Carlisle’s students into white society, Pratt refused to let them return to their homes for the summer and instead sent them to labor (outings) for white families.

Outings prevented students children from returning to their families and their reservations, where it was feared they would return to their traditional lifestyles or, as it was described, “go back to the blanket.”

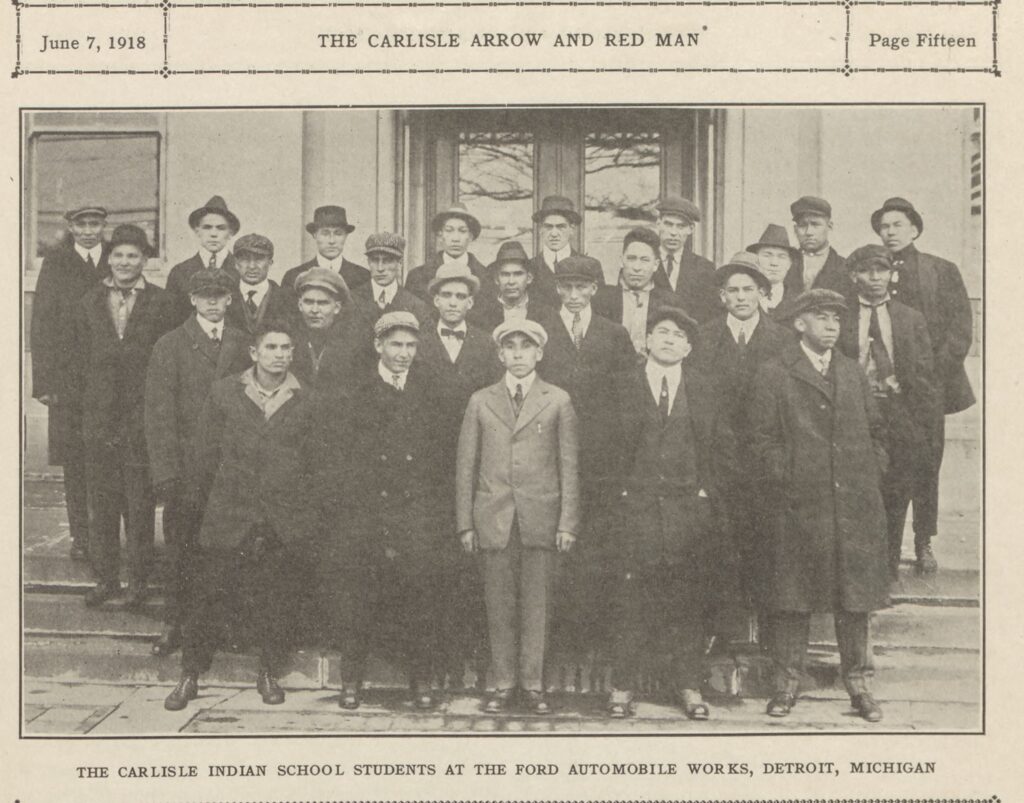

Sometimes outing patrons seemed to accept Indian students with open arms, adopting them as their own children, taking care of them when they fell ill and affording them headstones when they died. Some would have students in their homes throughout the entire year where they attended local public schools while continuing to work for their patron families.

Read more...

Sometimes Carlisle students made lifelong friends with their patron families, forming relationships lasting over generations. Other times, Carlisle students never went back home, instead settling in Pennsylvania.

Mohawk student, Jacob Jackson, stayed in Carlisle after the school closed in 1918, possibly on the farm with his outing patrons. At some point he worked on another farm and stayed in the Carlisle area until he was in his early 40’s. According to interviews, it appeared that he was accepted as part of their family. When he died after being hit by a car, the farm family wanted to lay him to rest and pay for his funeral expenses. Apparently, the county didn’t agree with that plan and instead he was buried in the town cemetery, with no marker and no memory of who he was.

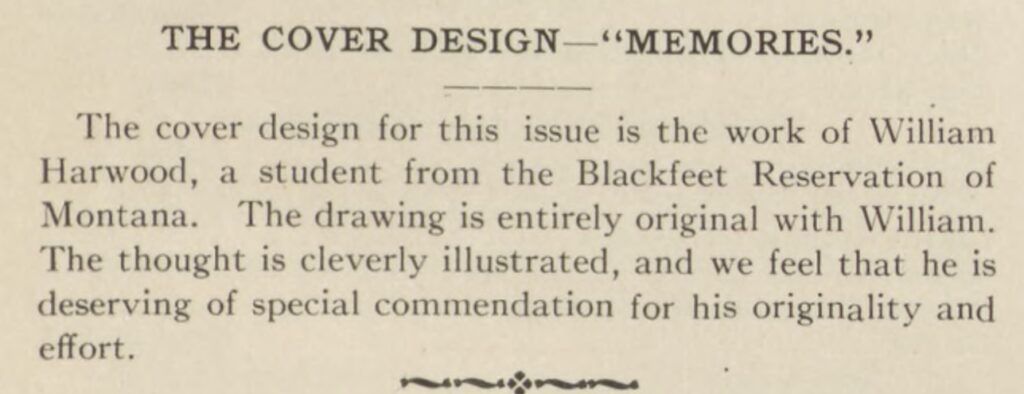

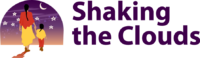

Girls typically worked as domestic servants while boys were often farmhands for patrons throughout Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Thousands of Carlisle students were sent to work over the years, some as far away as Detroit to work at the Ford auto factory, and some at the Hershey’s chocolate factory in Pennsylvania. The majority however, labored as farmers and housekeepers.

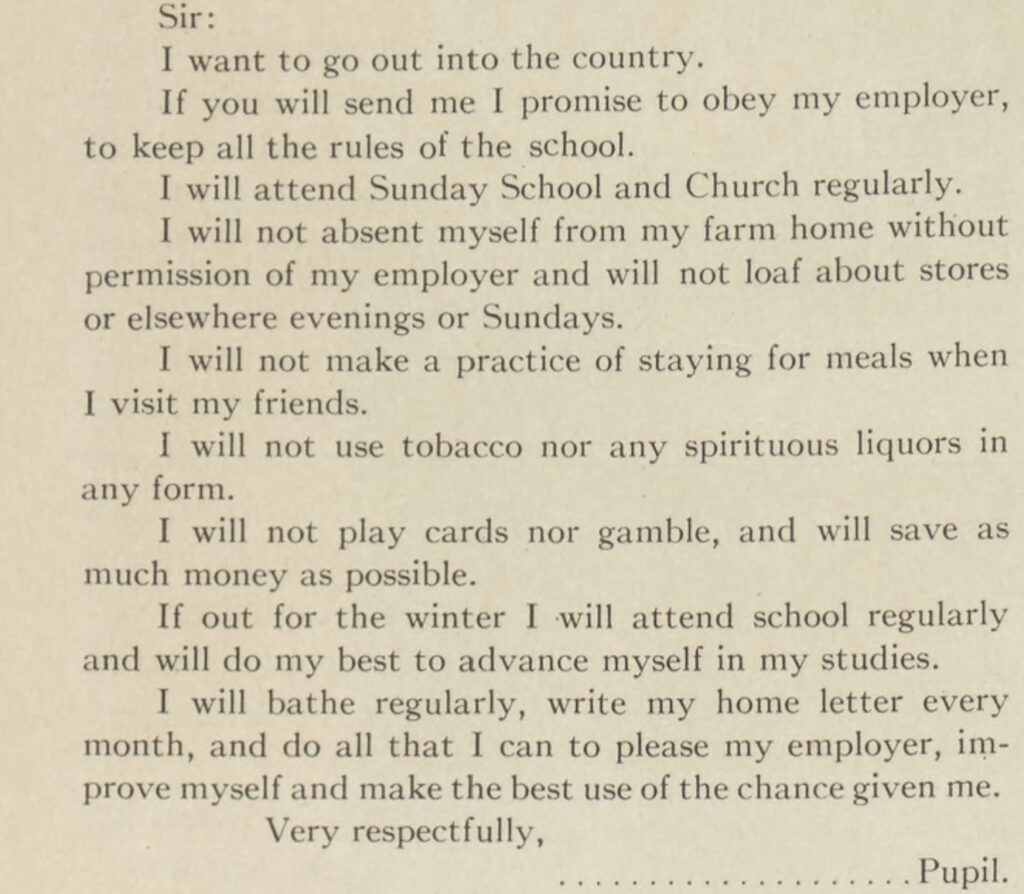

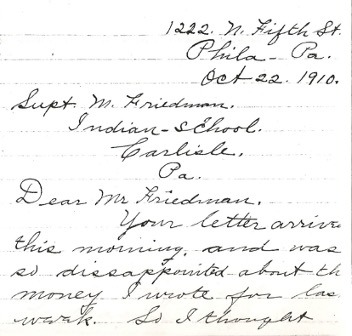

Strict rules were in place for how Outing students could access and spend their earned money:

Read more...

“Do not allow the free use of money. Advise and assist in the purchase of clothing and other necessaries, which charge up at the time. Give a small amount of spending money occasionally if asked for, but if it is spent for useless articles withhold it and advise me. Pupils are expected to save at least 75% of their wages when regularly at work. After two weeks trial, talk with pupils and correspond with me about wages, which are to commence when pupil is received, but what is customary in your vicinity for like service should determine the matter. When returning to the school give enough money for transportation and send the balance to me by mail…“

(Pratt, mss s1174, Box 30, Folder 815, c. 1900; qtd. in Bell, “Telling Stories out of School,” 169. In L., 2016, p. 110).

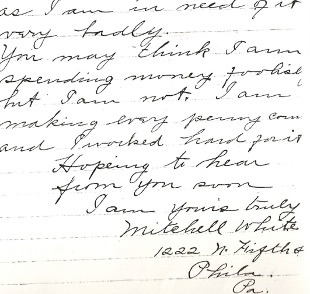

Arionhiawa:kon worked on several farms throughout Pennsylvania and New Jersey during his outing placements. While work on a farm in New Hampton, NJ, he stayed with the Riddle family, attended the local public school and worked on their farm.

Read more...

My grandfather wrote to the school at least twice asking for the hard earned money he made from working on a farm. He had already left Carlisle and was doing what he had been trained to do— work, earn money, and participate in the American economic and social structure. He needed his money to buy a suit for his new job and had to prove what his money would be used for. Strict rules about money management were meant to teach students to become self- sufficient farmers and homemakers who would become good and productive citizens.⁵ (White, L. 2016., p. 111).

Students were mostly trained to be domestic servants and farm laborers, not teachers or lawyers, which was a contradiction between the outward appearance of the assimilated Indian living in white society and the ways in which the outing program simultaneously ensured Indians’ inferiority. The Indian could be like the white man in dress and behavior, but the occupation and social status of the Indian would never be equal to that of this white counterpart. (White, L., 2016, p.108).