“Tell them we didn’t have a choice.” ~

Arionhiawa:kon

It was 2009 and I had just finished my PhD at the University of Arizona and spent a year at the University of Illinois for a Postdoctoral position with the American Indian Studies department.

Read more...

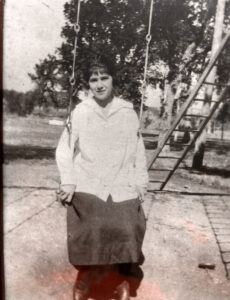

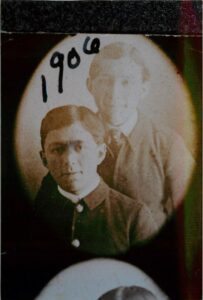

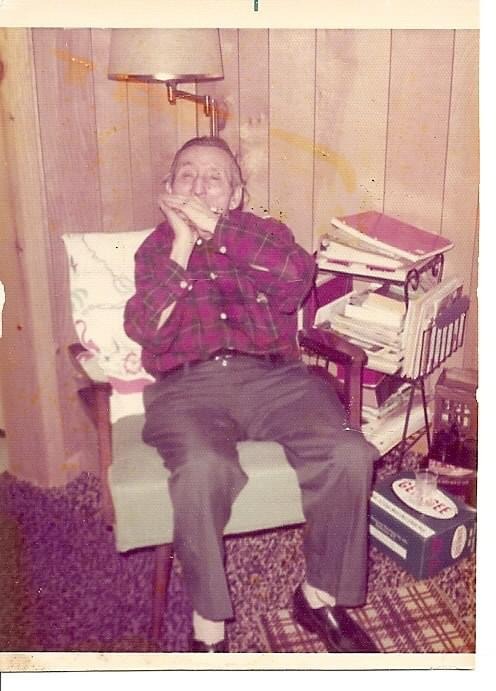

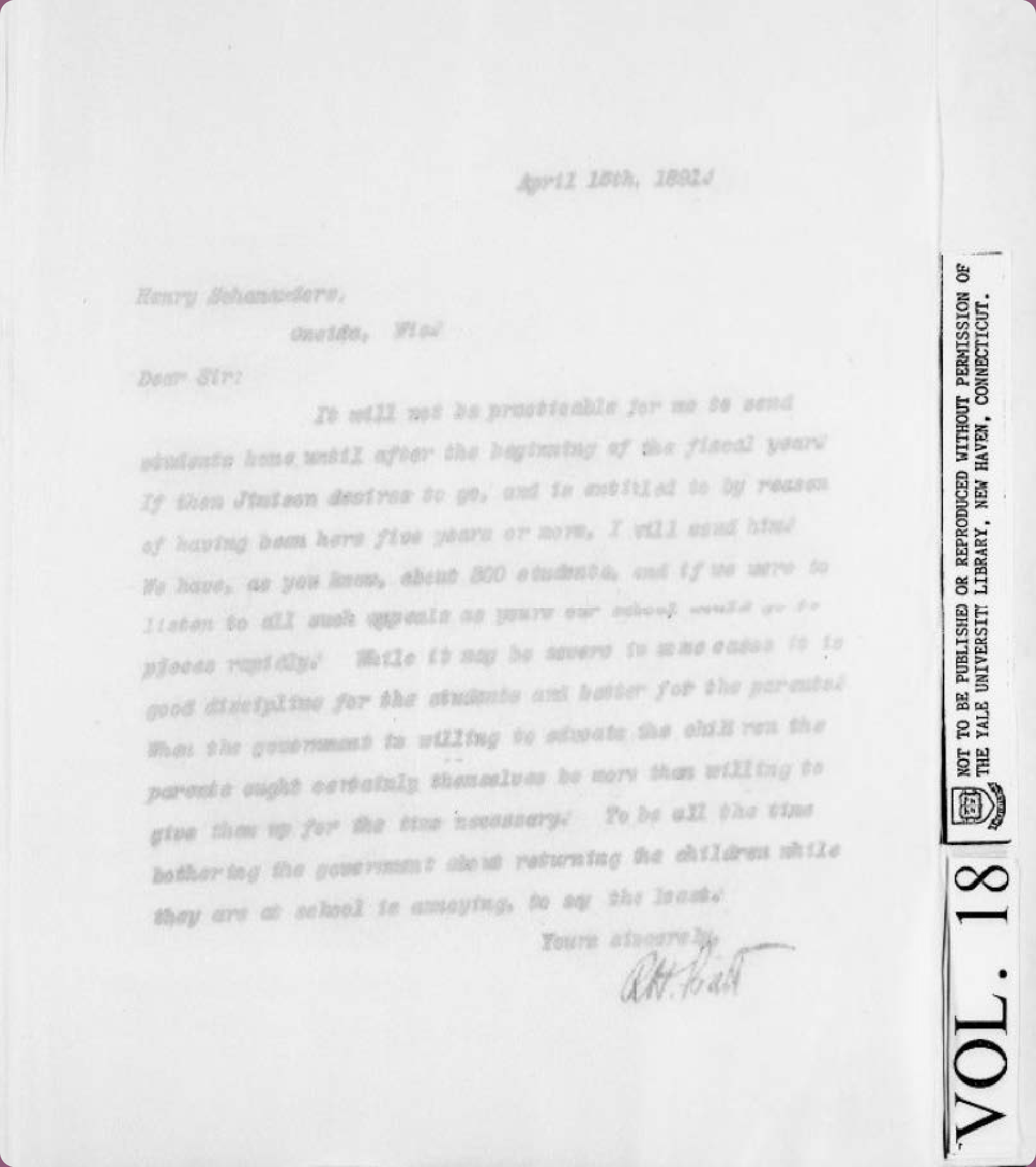

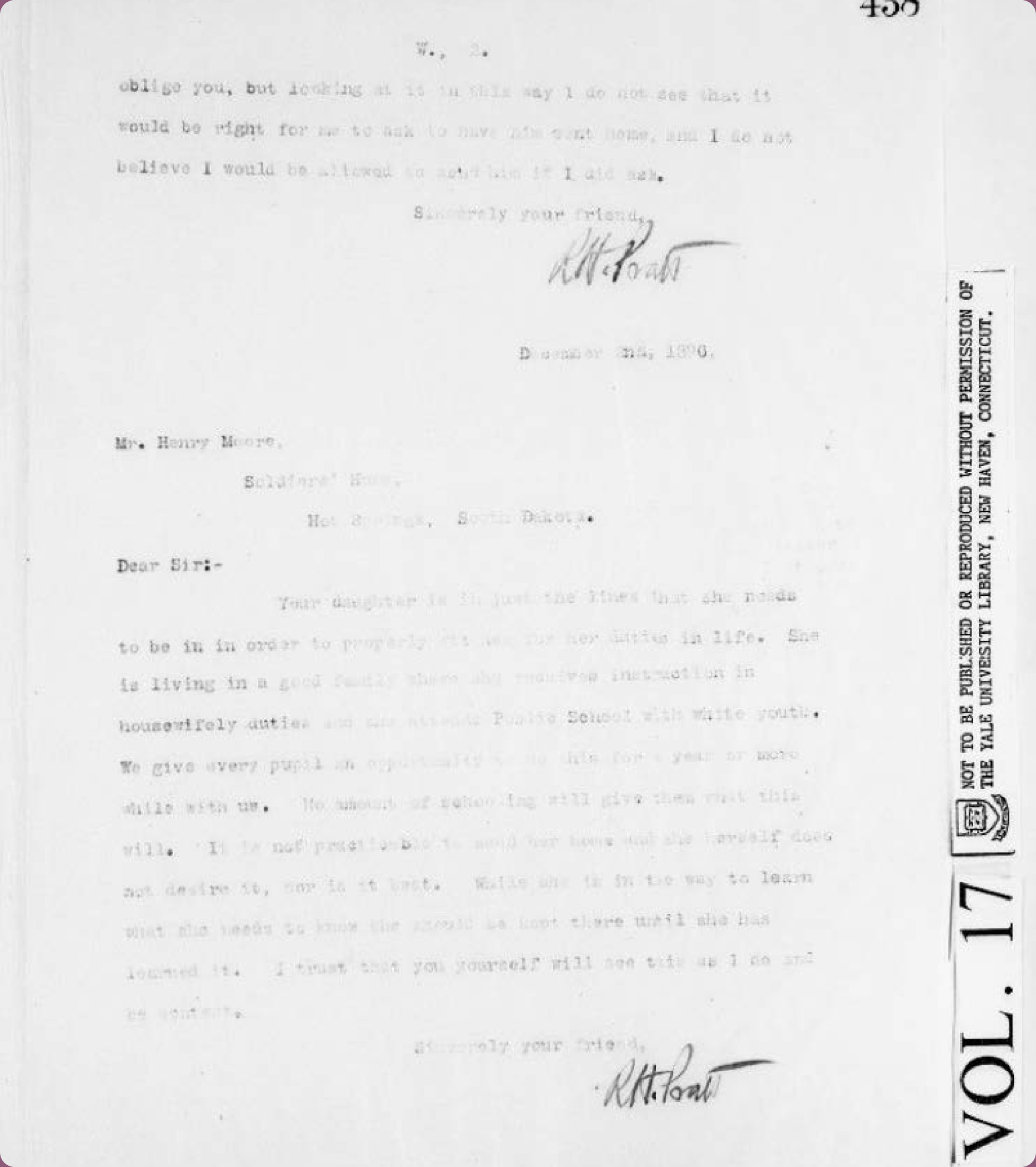

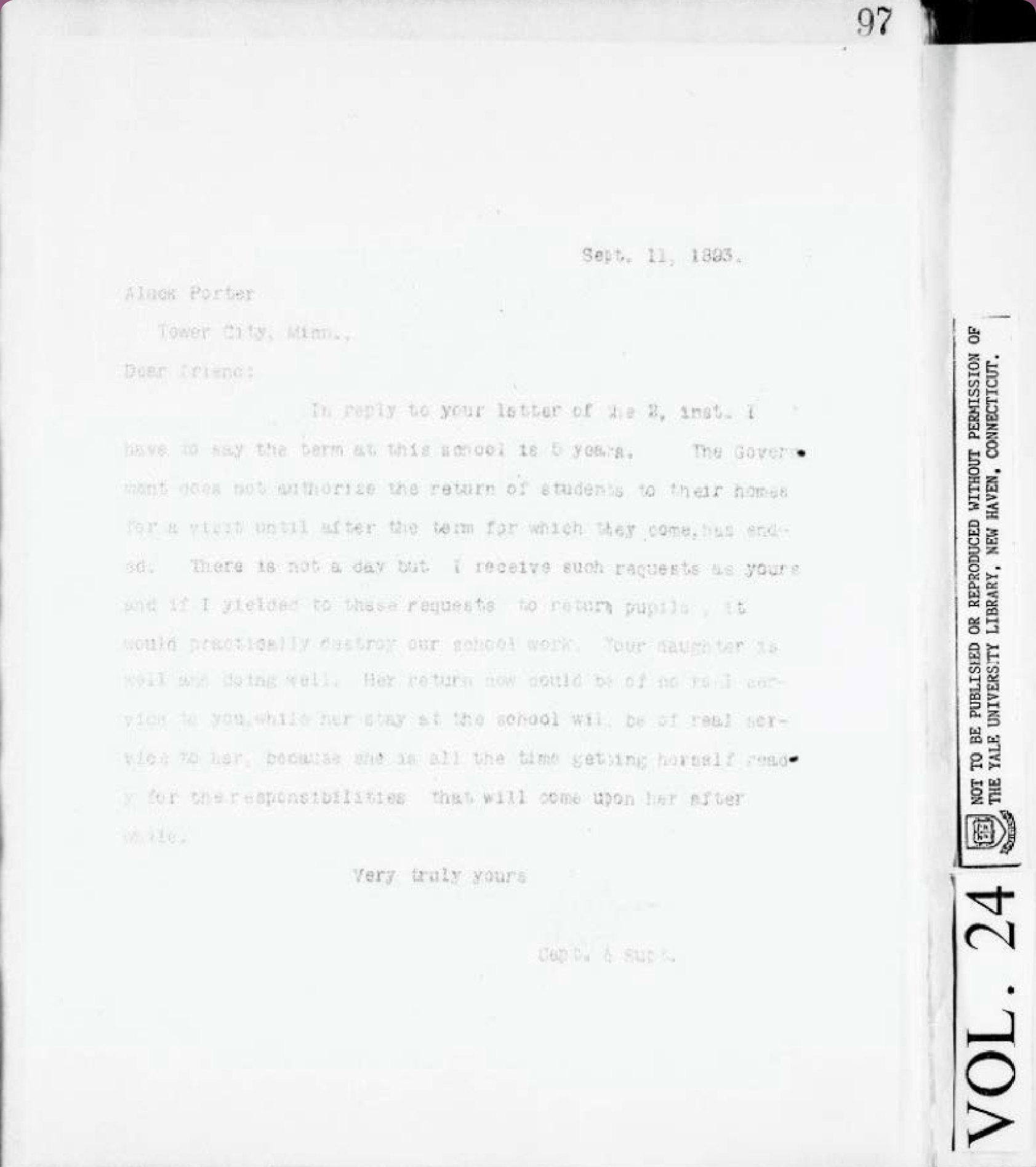

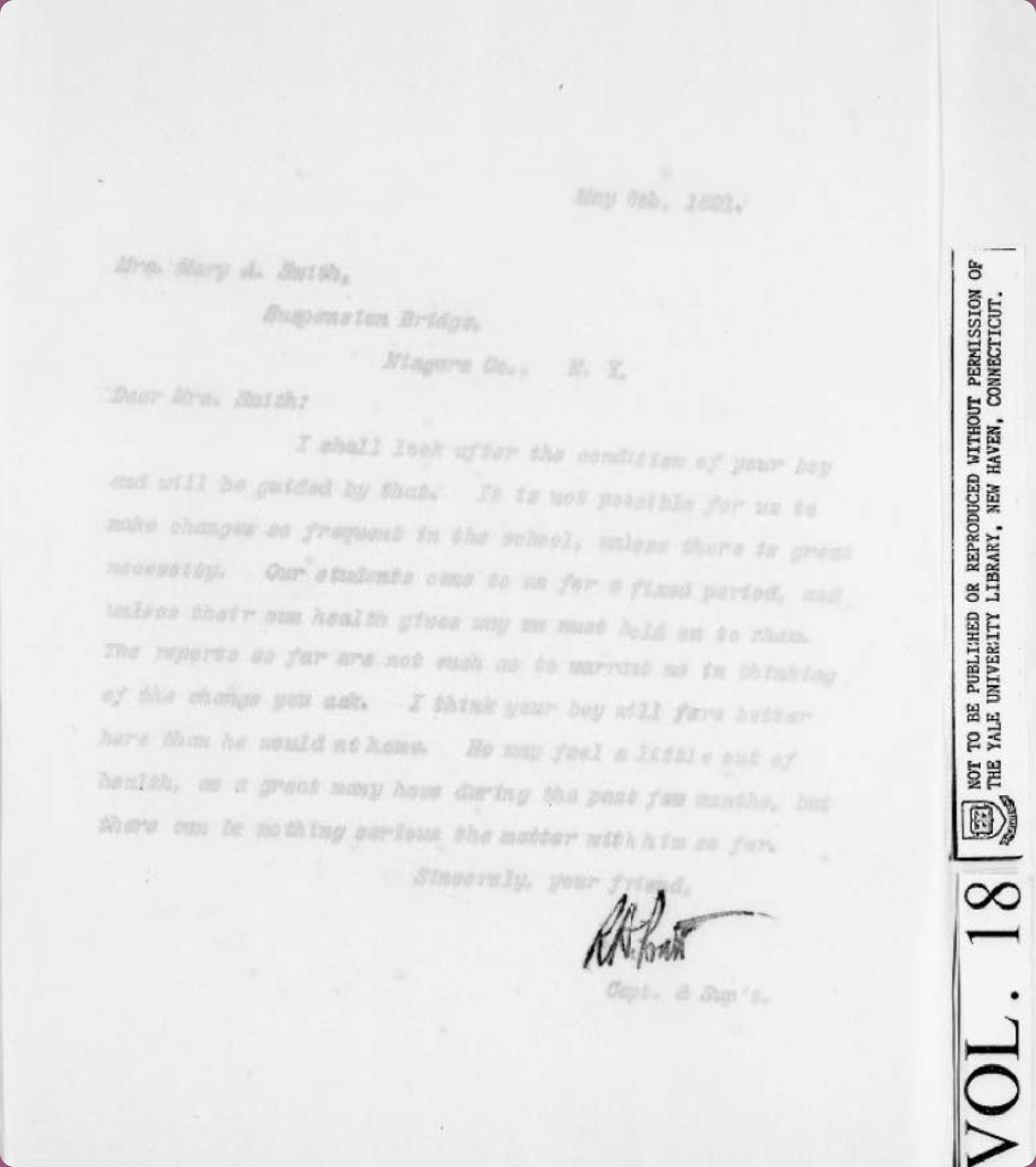

I was heavily grieving the loss of both of my parents and had inherited my father, Louis White’s extensive photo collection. I was preparing a lecture on the Carlisle Indian School and had immersed myself in family history, photos, and everything I had gathered over the years about Carlisle.

The night before the lecture, my Grandpa paid me a visit. I asked him, “Grandpa, what do you want them to know?” He plainly replied, “Tell them we didn’t have a choice.“

I thought about what he meant for a long time. Either they lived their young lives hungry without much hope for their futures OR they venture into the unknown with promises of three meals a day, and an education that would help secure their place in an rapidly changing society. But they, like many others, would pay the price of leaving their homelands, families, cultures, and languages behind; and their identities as Kanienkeha:ka. This was no choice.